A Case for Marina Abramović and Ulay, In the Name of Art and Love

by Elena Chen

“I have to say, from 12 years we lived together, 9 years was incredibly great. And then 3 years was really, really bad. But you know some people don’t even have these 9 years, we have to be really grateful for that.” --- Marina Abramović

When artists conjoin there is combustion --- an ignition of energy sourced from nothing less than creativity itself. What happens when artists fall in love with one another, when beyond the professionally personal there comes the personally professional? Artists create by using parts of themselves so everything they present requires an offerance of something incredibly personal. When their work is so deeply commanded by who they are, their love lives certainly come into the process of art production. This October, the Barbican Centre in London opened the doors to their long-awaited exhibition: ‘Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy, and the Avant-garde’, enlisting the work and lives of more than 40 duos (and a few trios) in a grand display of love, lust and labour.

The show may seem better in name than in person, as reviews have been deflated. Laura Cumming from the Guardian gave it 2 stars out of 5 and summarised it as “A huge survey of artist couples gets neither to the heart of their relationships nor their work.” Her account of the exhibit claims the content awkwardly balances between “art and biography”, where some relationships aren’t justified in the selected work shown and others seem too descriptive to have any art to show for it. For Cumming, despite the “premise of collaboration”, many of the chosen couples such as Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar, Marcel Duchamp and Maria Martins, were much less cooperative in profession than in relation. Cumming makes her own pitch for Anni and Josef Albers, whose relationship birthed mutual experimentations with colour.

This, however, is the case for Marina Abramović and Ulay, a couple who forged art history alongside romance, in their version of “art, intimacy and the avant-garde”.

Marina Abramovic and Ulay, Rest Energy, Performance for Video, August 1980

Marina Abramović is a household name in performance art. She may be the most famous performance artist ever. The wealth of literature on Marina Abramović comprises of biographies and reviews that both condemn and praise the extremes she reaches. Some are certain she runs a satanic cult and others experience the changing impact of her work. Whatever the opinion, everyone has an opinion of her. She’s charming. You can see it here. And here. And here. And here. Not in a traditional sense. In a dry, unabashed, raw intensity that can land as charismatic or pedantic. She always has so much to say. In interviews, online, in public, to the public. But Ulay, is much less media-present. Many of his public appearances are tied to Abramović, whether it’s his victory over joint artworks or his scenes in The Artist Is Present, Ulay is more than often labelled as her “ex-partner” and “former lover”. In spite of this, his contributions to the photographic practice and performance art should not be underestimated. Their love story is tumultuous, scandalous, beautiful, and epic. A German photographer meets a Serbian artist in Amsterdam, 1975. And because their love was in many ways also their art, in describing their love art must also be included.

Marina Abramovic and Ulay. 1977 Breathing In/Breathing Out

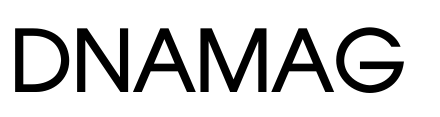

It’s not hard to imagine the volatility that could have resulted from their work and personalities. In a video by the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Ulay described his first impression of Abramović as “fatal” and Abramović held a great curiosity for Ulay. She who under a 10pm curfew in Yugoslavia and he who began experimenting with crossdressing in Amsterdam. A year before, in Italy, she had performed “Rhythm 0”, a performance art piece involving 72 objects and an audience told she would take full responsibility for anything that happened to her for the next 6 hours. They could do anything to her with those objects, and she would take responsibility for it.

She wanted to make a statement towards the moments of evil in people. That year, Ulay was taking Polaroids of his embodiment of drag that both paid tribute to the editorial demands of fashion photography and asked important questions about identity.

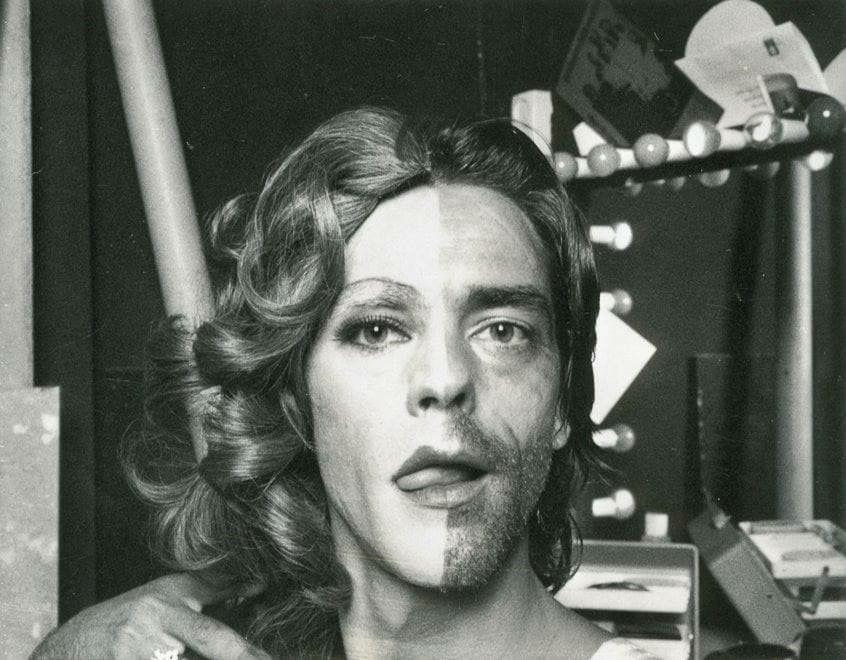

Their work communicate on an emotional level. Each uses their own body as a canvas to project experience. They embody their art. After 1975, their work becomes more this embeddedness than ever before.

In 1976 their relationship began, when Ulay first nursed Abramović’s wounds. That same year, Relation In Space was performed. The two artists ran into one another’s naked bodies for an hour in hopes of merging together without ego as as third energy --- that “self” --- until Abramović fell from exhaustion. In 1977, they began living together in a black van with their dog Alba, and continued to do so for the next 5 years. In the van they made Relation In Movement, driving 365 rounds in an emptied pool of a museum from day to night, then dusk to dawn. They found sustenance in the mountains they traveled through, made their own cheese and knit pullovers to wear. There was a (gendered) division of labour: Ulay took care of money as Abramović cooked and cleaned. They lived together, “and then [they] would get together to make art.”

“What we did in performance was absolutely the opposite of how we understood, how we lived and loved each other. Completely opposite.” --- Ulay

Whatever this may mean to the viewer: an interchange of individuality, two dependents codependently exhausting their resources, a source of life in love, a test of endurance and perseverance...One can hardly engage with a performance as such without incurring a reaction. The textured palpability of their work comes from an utter trust that enabled such collaboration, the same trust that allows for ideas contesting existential and ontological questions of human relation to manifest with greater clarity in collaboration than otherwise. Without being so in love with one another, being so accepting of one another, so trusting of one another, how could their work have delivered such poignant messages simplistically? In their love and labour no one is lost, both are simply made more aware of an artistic vision and their own desires to accomplish them together.

In 1981, they began Nightsea Crossing.

After 13, 14 days of silent, static, fasting, Ulay stood up. He was in pain from the piece. Marina continued. Ulay said that she could not continue the piece without him, but she did not see a reason not to. And she continued, with an empty chair in front of her. They were met with limitations --- different limitations.

For Ulay, from the 1980s onwards, the Ulay-Abramović/Abramović-Ulay duo became an institute. As an anarchist, it went against him. For Abramović, it was the “normal result of so much work” they had done. Ulay said that they had become part of art history but he had never intended for that to happen. People were pitting the two against each other in efforts to distinguish the better artist from the other, but it wasn’t a game to Abramović.

“To me it was completely fine because when he left I’m just, exactly what I’m doing, the same thing, I never stop. And he want something else and I couldn’t recognize that.” --- Abramović

They were misaligned.

In 1986, they stopped communicating.

In 1988, they performed The Lovers.

Each artist was to walk from one end of the Great Wall of China towards one another to meet in the middle. It was originally devised that they would marry when they met, but it became the piece with which they said goodbye.

They didn’t speak for about 20 years after.

In 2010, the MoMA held a retrospective on Marina Abramović. Besides recreations of her past work performed by other artists, she herself sat at a square table, motionless, everyday for 8 hours, for over 90 days.

Their relationship hasn’t ended. If not lovers, they were also involved in a lawsuit in 2015 over undue royalties over shared works that Ulay claimed were never paid him. In 2018 they announced they would be co-writing a memoir. They’ve hated each other, loved each other, withdrawn from each other, accepted each other, honoured each other, and supported each other. No matter the relation, there was art. In the last minute and ten seconds of the Louisiana Museum film, both artists reflect on their relationship now and the different natures of the relationship they’ve experienced. In their admiration of the story they share and the beauty that this trying and tender relation is remembered with, I would argue that whilst their work was born from love, their love was and is in itself, unknowingly, a piece of work.